A lack of legal safeguards for economic freedom

What we do for a living has a significant impact on who we are and how we turn out more so than almost anything else we do. This is something that has been known for quite some time; indeed, it could be said to be “deeply rooted” in American culture. And indeed, that’s what Fifth Circuit Judge Jim Ho said last month. However, it appears that the U.S. Supreme Court does not think this fundamental part of freedom is linked to the Constitution.

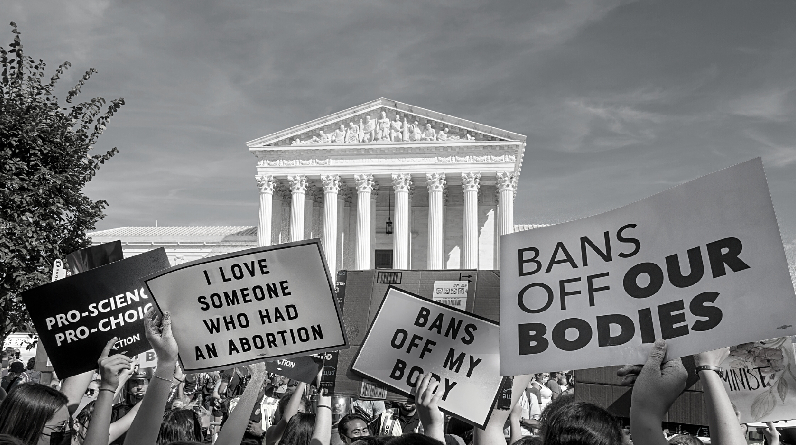

Implications of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade, went far beyond the realm of abortion when it was announced last summer. The question of how the U.S. Constitution protects liberty in general lingered behind the headlines. Even though they disagreed on the morality of abortion, the two sides in Dobbs presented a distorted view of freedom by establishing arbitrary boundaries. There was nothing novel about this practise; the justices have engaged in it for decades. However, the decision gave direction for the future, especially in regards to the right to earn a living, and perhaps even some hope, to those who believe the Constitution broadly protects liberty. The Supreme Court has indicated that it may take a stronger role in protecting a right if it is shown that the right is “deeply rooted” in history and tradition. That is more true of the right to work, than it is of almost anything else.

Equal Protection of the Law for To What Amount Does

To begin, some history on the systems in place to safeguard our liberties: After the Civil War, the states were required to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment, which included the due process clause guaranteeing that no one could be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” It has long been accepted that the clause safeguards against the arbitrary deprivation of liberty, even when the legislature democratically passes a statute. Many have argued persuasively that the privileges or immunities clause of the same amendment is a more effective means of protecting most rights. Unfortunately, not long after its 1868 adoption, the Supreme Court effectively nullified the “privileges or immunities” language. There are, however, compelling arguments that the due process clause itself safeguards substantive rights. This would encompass a wide range of rights and privileges not explicitly guaranteed by the Constitution, such as the right to pursue any line of work, the right to dispose of one’s property as one sees fit, the right to rear one’s own children, the right to cultivate one’s own food, and the right to indulge in unhealthy snacking while watching television.

For a while, the courts even acknowledged that many of these rights, including the right to a livelihood, were encompassed by the concept of due process. This didn’t mean any law that curtailed these liberties was invalid, though. It did, however, imply that the purported necessity of a law by a state was weighed against the potential negative impact on people’s freedom. Although this safeguarding rarely occurred, when it did, it was often genuine: the court considered the facts, evaluated the legislative motivations, and frequently found laws to not advance legitimate governmental interests but rather to violate individual rights. While this approach typically focused on protecting economic freedoms, it has also been used to defend the rights of parents to choose how and where their children are educated. In addition, the Supreme Court, in the 1920s, began applying the Bill of Rights to the states as part of the same “due process of law,” which had previously only applied to the federal government. These days, when we hear about the Bill of Rights, we automatically associate it with the Fourteenth Amendment and its application against the states. The Court has extended them to the states because they are fundamental to individual liberties and are safeguarded by the Due Process Clause in the same way that the Court has traditionally safeguarded a wide range of other rights that are not explicitly listed in the Constitution.

Although there is a New Deal, not all deals are created equal.

During the New Deal, the Supreme Court largely stopped defending inalienable rights. Although they didn’t give up entirely, the justices now only fight for a minority of their original causes. The right not to be sterilised and the freedom to travel are just two examples of the unenumerated rights that fell into these categories, along with other, seemingly unrelated rights. Additionally, it appeared to leave unaffected parents’ constitutionally protected freedom to choose their children’s educational environments. Laws regulating everything else were only deemed unconstitutional if they violated individual liberties to a “extreme” degree, while those pertaining to the aforementioned areas received “heightened” protection. This included the development of the “rational basis test” and the enormous challenges most Americans face when attempting to defend economically marginalised rights in federal court today. According to this standard, a judge only needs to conjure up some hypothetical facts that might show how a law serves a legitimate government interest to rule that it is constitutional.

The Supreme Court’s inconsistent defence of inalienable rights expanded but remained narrow in the 1960s and 1970s. The court upheld rights like access to contraception, abortion, and family-based housing. The assortment here was rather random. For instance, it’s not clear why these rights were protected while the right to a livelihood was left out. A cynical (and likely accurate) interpretation is that the court simply upheld government interference in the economy. Whatever the case may be, the Supreme Court has consistently failed to defend a wall between economic and other forms of freedom. They continued onward without stopping.

As a result, “liberty” was not universally safeguarded as promised by the Fourteenth Amendment; rather, it existed only in isolated enclaves.

Refusers of Dobbs, On Both Sides

Here we reach the Dobbs trial. Should abortion remain one of these disconnected areas? was the question before the Supreme Court. Justice Samuel Alito briefly wondered why there isn’t just a general “right to autonomy” in the court’s opinion. If the ocean needs protecting, then why is the court only protecting islands that aren’t even in the same ocean? That might encompass every one of the privileges I just listed. This was shot down by the court because it “would prove too much. Those criteria… could licence fundamental rights to illicit drug use, prostitution, and the like.”

To counter that, though, you’ve presented a ridiculous strawman. Even if the Supreme Court were to recognise an abstract right to “autonomy,” this would not render existing drug and prostitution laws null and void. It would merely imply that the court would strike a balance between state interests and the individual’s freedom of action. In fact, the court could take this approach to the abortion issue, which is unlike any other because of the “potential life” at stake. The court instead chose to uphold a few isolated rights that are guaranteed by the constitution while leaving most “liberty” activities unprotected or only partially so.

Also, moving forward, the court re-adopted a test it had previously articulated, called the “Glucksberg test” after a case in which it rejected a right to assisted suicide. An unenumerated right would meet the criteria for enhanced protection if it were “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty” and “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition,” in addition to being carefully defined at a certain level. The right to “bodily autonomy” or “economic liberty” is, therefore, too broad and abstract.

This has repeatedly stymied arguments in lower courts that certain liberties the court has not already recognised under Glucksberg are themselves protected. Patients who wanted to try out experimental cancer drugs that the FDA had not yet approved argued that the right to try to save one’s life with drugs is a “deeply rooted” right that the FDA had violated in this case. The right was narrowed by the court to cover only drugs at a certain stage of the FDA approval process, which the court deemed not “deeply rooted” (and obviously so, considering those levels are recent regulatory inventions).

Conspiracy To Suppress Economic Freedom Through Revisionist History

Just as the Dobbs majority had its strawman, the Dobbs minority did as well. Justices who dissented argued for the long-standing general right to bodily autonomy, which they defined as a restriction “on a State’s power to assert control over an individual’s body and most personal decisionmaking.” As a matter of fact, the freedom to manage one’s own body is a fundamental right. However, the dissenting view failed to explain why the right to bodily autonomy does not encompass the freedom to make economic decisions. The only explanation it offered was a very poor interpretation of history, claiming that the Great Depression “disproved” the “assumption that a wholly unregulated market could meet basic human needs” and thus justified the abandonment of the safeguards for economic freedom mentioned above.

The very idea is laughable. To say that the Great Depression “disproved” the Supreme Court’s limited efforts to protect economic freedoms is misleading. It’s possible that some people in the 1930s thought this during a crisis, but for these justices to continue to believe this in the present day is astounding. Despite what many on the left would have you believe, the so-called Lochner era of the early 20th century (named after the 1905 case Lochner v. New York) was not one in which the court dictated a “wholly unregulated market.” The dissenters are on the right track when they argue that individual liberties are guaranteed by the Constitution. However, it lacks principle and cannot be defended to not allow that protection to extend to economics.

It is a fundamental human right to be able to support oneself economically.

From Dobbs, what can we learn? It does not significantly impact other rights that are not explicitly stated. Because the ability to make a living is not a “favoured” right, it is difficult to challenge illogical economic regulations using the rational basis test. Dobbs is depressing because it confirms that no branch of government appears eager to provide additional safeguards for citizens’ rights.

See Also: The London Fashion and Technology Pioneers

However, that reserve can be put to the test in a variety of ways. Not only has Dobbs piqued the court’s interest recently, but history in general. Growing your own food, starting a business out of your garage, and feeding the homeless are all examples of libertarian practises that are “deeply rooted” in our history, but the Supreme Court seems reluctant to embrace economic liberty and other unenumerated rights (a right local governments shamefully violate). Specifically, last month, Judge Ho wrote that “various scholars have determined that the right to earn a living is deeply rooted in our Nation’s history and tradition,” so this is something he did talk about.

No doubt, in upcoming cases involving civil rights, the background of the particular right at issue will be presented to the courts to see if that draws more attention to the case. Even if it fails to establish a particular freedom as a “fundamental right,” the rational basis test may still move things in a direction more protective of rights. One of these fundamental rights is the ability to find gainful employment. In the coming years, we will find out if the past can teach us anything about expanding our bastions of freedom.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.